In this interview, News Medical speaks with a PhD researcher at LifeArc Natahsa Bury about how targeted protein degradation could emerge as a powerful new strategy to combat antimicrobial resistance, particularly in hard-to-treat gram-negative bacteria.

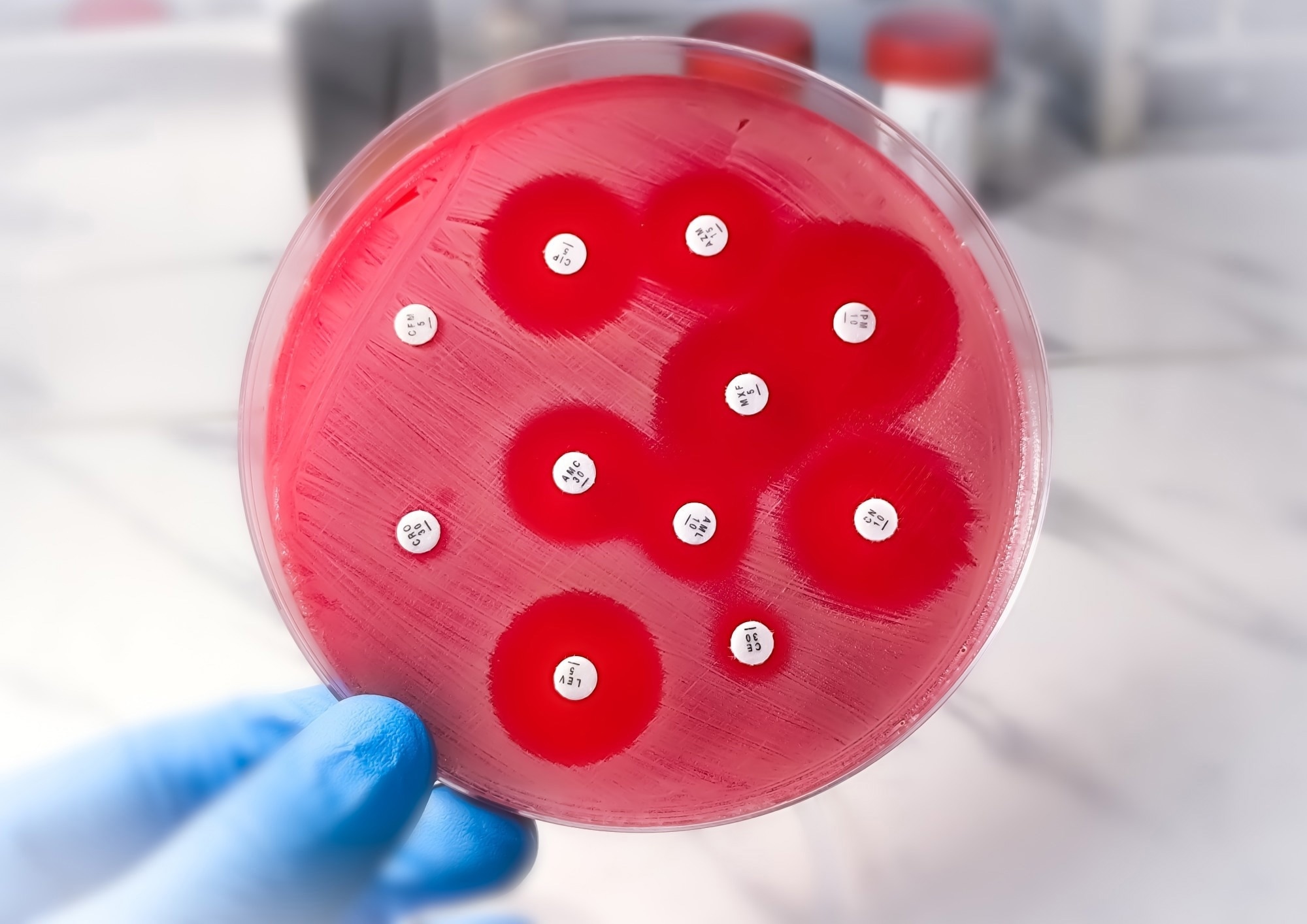

Image credit: Saiful52/Shutterstock.com

Image credit: Saiful52/Shutterstock.com

Can you please introduce yourself and your role at LifeArc?

As part of my Biochemistry degree at University of Leeds, I completed an industry placement at LifeArc. This was my first introduction to LifeArc as a company, and after graduating, I returned and began working there.

Targeted protein degradation is a relatively new approach and not something I had heard of before starting work in this area two years ago. Since then, my interest in the field has grown significantly. My work with LifeArc and the University of Glasgow focuses on antimicrobial resistance. Through this PhD, supported by a fellowship from the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851, I am exploring targeted protein degradation as a novel antibacterial strategy in bacterial systems. My ultimate goal is to develop tools that can advance this research and enable new drug discovery approaches to combat antimicrobial resistance. I am extremely grateful to be part of this collaboration and to have the opportunity to contribute to an area where there is such a significant unmet need.

Why is antimicrobial resistance considered such a critical global health challenge?

Bacteria are evolving to resist the antibiotics we currently rely on, making infections increasingly harder to treat. The World Health Organization has predicted that by 2050, antimicrobial resistance could be responsible for up to 10 million deaths per year, overtaking cancer as a leading cause of death.

Tackling drug-resistant infections is a key focus of LifeArc’s global health efforts. There is a real urgency to develop new therapeutic strategies that go beyond traditional antibiotics.

What specific biological features make Gram-negative bacteria particularly difficult to treat?

The biggest challenge with gram-negative bacteria is their cell wall: a physical barrier creating a literal block that drugs need to get through. Unlike gram-positive bacteria, which lack this outer membrane, gram-negative bacteria have an additional layer of defence that makes them inherently more difficult to target.

Even if drugs do manage to cross the cell wall, gram-negative bacteria are also very well adapted at removing drugs. The bacteria often have efficient systems known as efflux pumps to pump it straight back out again. This combination of the cell wall barrier and efflux pumps make gram-negative bacteria especially challenging to target with conventional antibiotics.

Can you explain in simple terms what targeted protein degradation is and how it works?

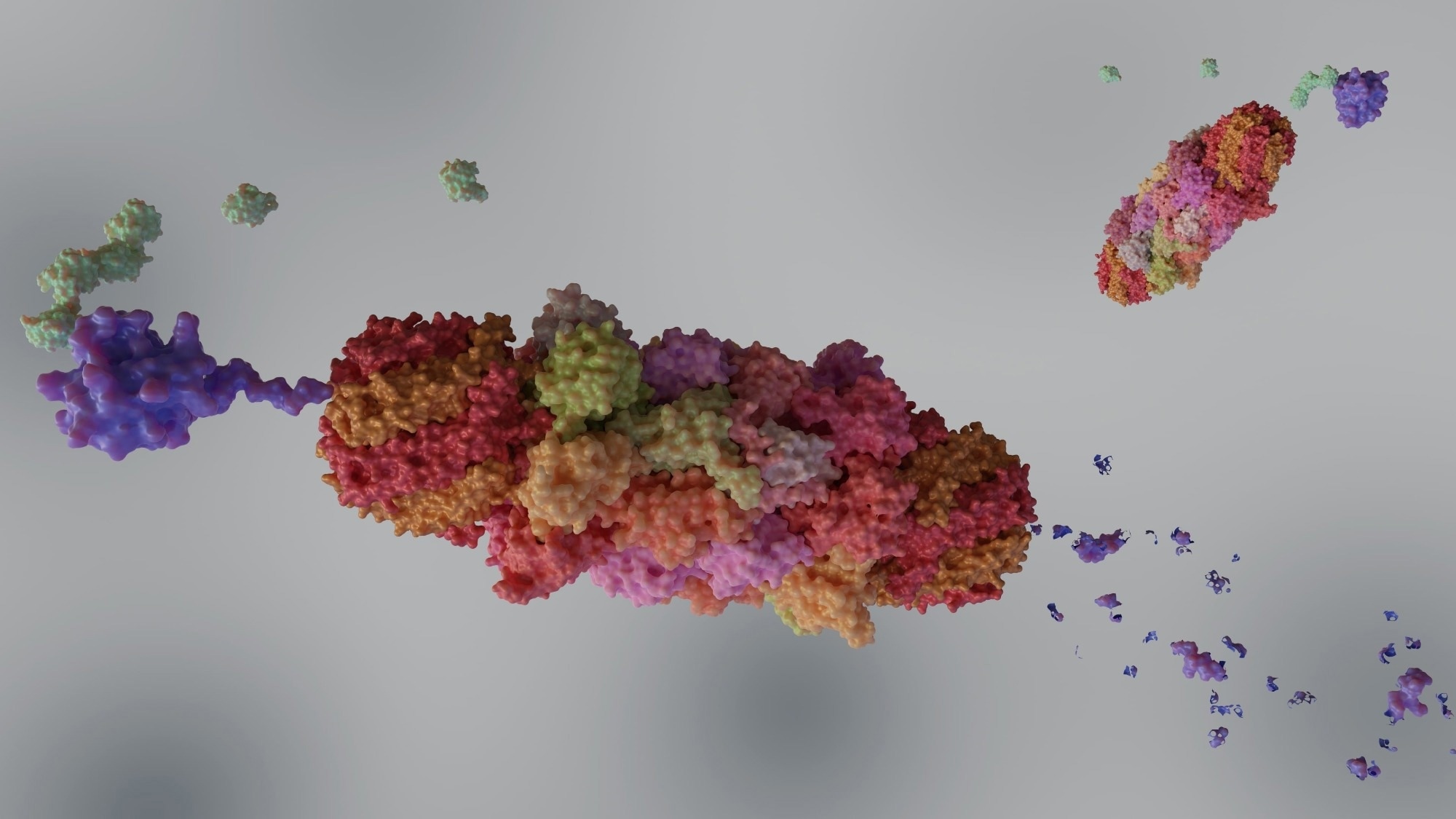

Our bodies already have natural machinery to clear old or damaged proteins: proteins such as haemoglobin or keratin are constantly being replaced.

Targeted protein degradation is an approach that utilises this natural clearance machinery. It targets a molecule that binds to a harmful or disease-causing protein and delivers it to the clearance machinery where the protein is removed from the system altogether. Instead of simply blocking the protein’s activity, you are actively eliminating it.

Image credit: Love Employee/Shutterstock.com

Image credit: Love Employee/Shutterstock.com

How does targeted protein degradation differ from conventional antibiotics?

The main difference lies in the mechanism of action. Conventional antibiotics typically work by inhibition, where a single molecule binds to a specific target protein and blocks its activity. As long as the molecule remains bound, the protein is inactive; however, if it dissociates, the protein can function again. This is a linear mechanism where typically one molecule inhibits one harmful protein.

With targeted protein degradation, one molecule can remove multiple copies of a harmful protein. Once the protein is degraded, it is gone, and the degrader molecule is free to repeat the process.

Eliminating the protein rather than simply blocking means one degrader molecule can eliminate many harmful proteins. This shift could potentially allow for lower doses and more durable effects, which could be beneficial for treating resistant bacteria.

Short on Time? Download the PDF to Read Later

Do bacteria present unique challenges or opportunities compared to mammalian cells when designing degraders?

Yes, and I think this is actually one of the most exciting aspects. Bacteria have protein degradation machinery that is similar to, but also distinct from, mammalian systems. We can take advantage of these differences and look to design drugs that are specific to bacterial systems and not recognised in human cells. This specificity could help avoid toxicity issues and improve safety in the clinic.

There are also differences between bacterial species. For example, gram-negative bacteria share similarities with each other but differ from gram-positive species. This opens up the possibility of designing degraders that are selective for particular bacterial groups or strains, which could help reduce side effects due to their specificity and reduce broad-spectrum antibacterial resistance mechanisms.

What technical or biological barriers currently limit the use of targeted protein degradation in bacteria?

The biggest barrier is still entry into the bacteria, particularly for gram-negative species. Their cell wall is a major challenge for conventional antibiotics, and it is likely to be the same for targeted protein degradation molecules. There are currently no examples of small molecules close to or in the clinic that recruit bacterial systems to degrade specific proteins, which is a technical barrier to early-stage fields.

For my PhD, I plan to account for this from the very beginning by building it into experimental design and molecule development. There are strategies, such as the Trojan horse approaches using peptides or iron receptors, that can help drugs cross the membrane.

Another challenge is resistance: targeted protein degradation is still at a very early, proof-of-concept stage in bacteria, so we do not yet know how bacteria might adapt. That is one of the reasons it is so important to develop molecules that can be tested and studied in more detail.

Targeted protein degradation has proved successful in cancer research. If we can exploit bacterial degradation systems in a similar way, it may be harder for bacteria to evolve around this mechanism because they need to regulate their own proteins for survival. Therefore, resistance to degraders could be slower than traditional antibiotics.

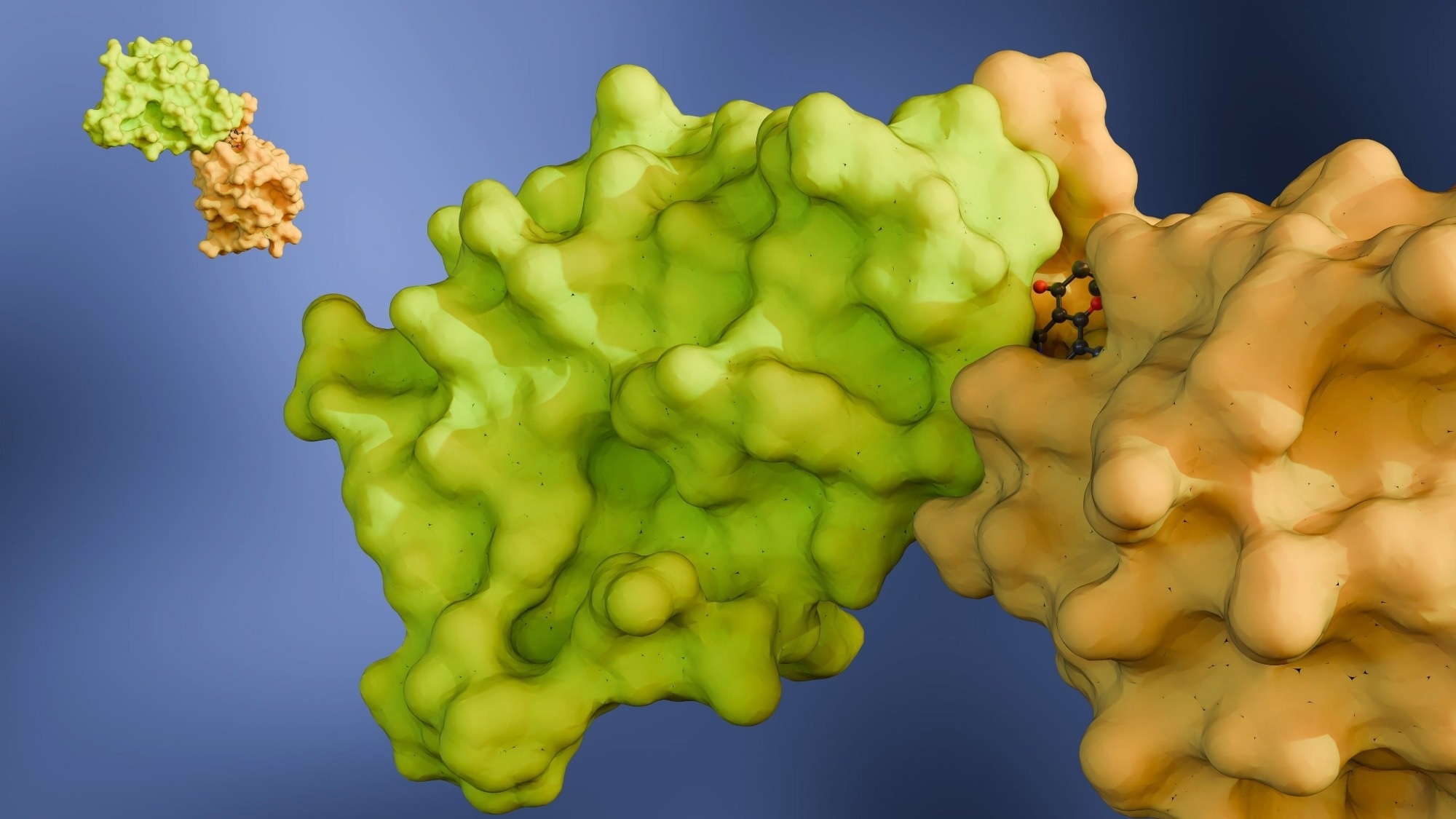

What does the term “undruggable targets” mean, and how could targeted protein degradation change this?

Traditionally, drug discovery has focused heavily on enzymes because they have well-defined binding sites that inhibitors can target. Over time, researchers have become very good at finding inhibitors for these kinds of proteins.

However, many disease-relevant proteins do not have these obvious binding sites, which has made them difficult or impossible to target using conventional approaches. These are often referred to as undruggable targets.

Targeted protein degradation does not rely on blocking a specific active site. Instead, it focuses on how efficiently a protein can be removed from the cell. This means many more proteins become accessible as potential drug targets, opening up entirely new areas of biology that were previously out of reach.

Image credit: Love Employee/Shutterstock.com

Image credit: Love Employee/Shutterstock.com

How do you decide which bacterial proteins could make the best targets for degradation?

This is a question I will be answering for myself over the next few years! Ideally, the target protein should be something the bacteria depend on for survival, such as proteins involved in replication or essential repair processes.

Working at LifeArc is a huge advantage because I am surrounded by experts in microbiology and drug discovery. I will be relying heavily on their experience to help identify suitable targets.

I am also very interested in the idea of targeting resistance mechanisms themselves. If we could degrade proteins that confer antibiotic resistance, we might be able to resensitize bacteria to existing drugs. That space is largely unexplored and very exciting.

At this early stage, we also need well-understood targets that can be used to validate the system. If degradation of a known essential protein leads to bacterial death, that gives us confidence that the approach is working before moving on to more complex disease-relevant targets.

How could targeted protein degradation change the future of antibacterial drug development?

My hope is that through my PhD, I can help build the foundational knowledge needed to understand how targeted protein degradation works in bacteria. Once that understanding is in place, antibacterial drug developers can start to explore its advantages more confidently.

LifeArc’s focus on translational science and unmet medical needs puts it in a strong position to take early discovery work and push it towards the clinic. If we can generate robust data and even early molecules, that could make this approach much more attractive to developers looking for new antibacterial strategies.

If targeted protein degradation fulfils its potential, how might bacterial infection treatment look in 10 to 15 years?

Ideally, we would have many more treatment options. Targeted protein degradation could help address resistance by allowing us to eliminate proteins rather than just inhibit them. We might see degraded versions of existing antibiotic targets, as well as entirely new targets that have no pre-existing resistance.

There is also the exciting possibility of drugs that remove resistance mechanisms themselves, helping to restore the effectiveness of the antibiotics we already have. Combination therapies will likely be key, as they are one of the best ways to slow the emergence of resistance.

From an early career perspective, it's incredible to be part of this. You hear about transformative technologies like gene therapy during your studies, and suddenly you find yourself working at the very beginning of a new discovery journey. It is really exciting to be able to contribute to that process.

Download your PDF copy now!

Where can readers find more information?

- The Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851 Industrial Fellowships are prestigious awards that support early-career researchers and engineers in pursuing innovative, industry-relevant research projects in collaboration with UK companies. Find out more here.

- LifeArc is a not-for-profit medical research organisation working to improve the lives of people with rare diseases and support promising initiatives in global health. Find out more here.

- This project is co-supervised by Dr. David France at the University of Glasgow. Research in the France group is focused on using bi-functional molecules to study a wide range of diseases from cancer to infectious disease. Find out more here.

About the Researcher

Natasha discovered her passion for early drug discovery through her Biochemistry BSc at the University of Leeds, learning a wide variety of techniques across many disease areas. She undertook a placement year during her BSc at LifeArc. Following her graduation with a First Class Honours, she joined LifeArc’s Chemical Biology team, where she has continued to develop her skills.

Source:

World Health Organization; Interagency Coordination Group on Antimicrobial Resistance (2019). No time to wait: Securing the future from drug resistant infections. [Online]. Availbale at <https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/no-time-to-wait-securing-the-future-from-drug-resistant-infections> [Accessed 31/12/25]